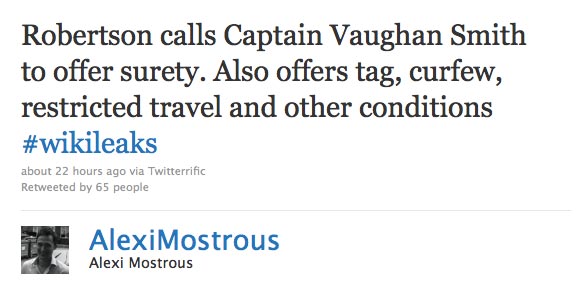

There was a great deal of excitement amongst media commentators and Twitterers during the bail hearing of WikiLeaks’ editor Julian Assange. As if Assange’s second bail attempt wasn’t enough of a news story, the judge at Westminster Magistrates’ Court gave permission for those watching in the court – specifically the Times’ special correspondent Alexi Mostrous – to tweet from court. Mostrous and journalist Heather Brooke’s updates from the scene were fascinating to follow:

There is no statutory ban on tweeting form court, as the Guardian’s Siobhain Butterworth explains in this excellent piece from July:

The Contempt of Court Act 1981 does not allow sound recordings to be made without the court’s permission. It’s also an offence to take photographs or make sketches (in court) of judges, jurors and witnesses – although the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 says that doesn’t apply to the supreme court. Since there isn’t a statutory ban on creating text by means of electronic devices, it surprises me that journalists and bloggers haven’t already lobbied British judges about reporting directly from the courtroom.

Speaking to Journalism.co.uk, barrister and former government lawyer Carl Gardner explained that there is the idea that jurors should not Twitter, “which raises particular issues of its own”.

What I think the courts don’t want is people using devices that make noises, or typing constantly, or even getting messages that make them keep getting up all the time. That I think is the reason for the normal court etiquette of switching off phones (silencing isn’t good enough; as in cinemas, people forget and trials end up being disrupted). So if a judge was sure people could tweet silently and that it wouldn’t disrupt proceedings, it wouldn’t amaze me if he/she permitted it.

I think tweeting from court could be a good development – subject to certain restrictions, such as jurors not looking at Twitter while on a case. I worry a bit though that it’s an unsatisfactory half-way house to transparency, though. People can tweet misleadingly and selectively, even without meaning to. For live cases of special interest like Julian Assange, what we really need is televised justice. Good reporting will do for cases of less immediate interest.

Claims that yesterday’s tweeting from the Assange hearing was a first in UK courts need a bit of explaining. It may well have been the first time a magistrate or judge has expressly given permission – although it was in response to a question from Mostrous and not an unprompted declaration. Several legal commentators I have spoken with suggest this, but it is difficult to track and the Justice Department, on the face of it, does not seem to keep a database of such decisions.

As there is currently no statutory ban, there have been previous occurrences of live-tweeting court cases in the UK. Ben Kendall, crime correspondent for the Eastern Daily Press and Norwich Evening News, for example, tweeted from within the courtroom when covering the John Moody murder trial in August. As he told Journalism.co.uk, he didn’t ask the judge for permission to tweet as there’s no ban, he has a good relationship with the court and “figured they’d pull me up on it if there was a problem”.

But Assange’s hearing was a significant case to be allowed to tweet from nonetheless – but what are the pitfalls and benefits of live-tweeting judicial proceedings? The UK Human Rights blog has this to say:

Despite its sophistication, in an ordinary case with no reporting restrictions in place, tweeting does not, on the face of it, pose any danger to the administration of justice. Rather, the ability for people to produce a live feed of selected information from a hearing could improve public understanding of the justice system. But it is by no means an ideal channel through which to communicate details of a complicated hearing.

It is unsurprising that the case of an man credited with improving transparency in government (while causing headaches for diplomats, soldiers and spies) could result in a watershed for the use of social networking in court. Perhaps the slow but steady opening up to social media by judges will eventually lead to a softening of the attitudes towards live video feeds. And that would mark a huge improvement for open justice.