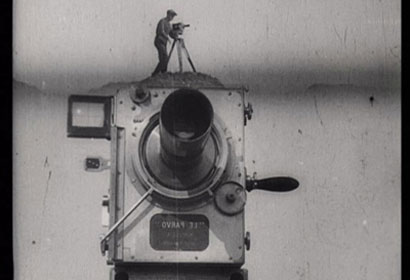

Still from 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera directed by Dziga Vertov, via Wikimedia Commons

I was asked to give a talk to a BBC Global Video away-day on the future of video, looking at what their audiences will be watching in the coming years.

The Global Video department was launched last year and makes video to run cross-platform in multiple languages on all the BBC’s Global News outlets: World News, BBC.com and 27 World Service language services. The team never makes a video just for one language or site, changing the voiceover and translating the film into two or more languages.

What will audiences be watching?

There are countless examples of innovations in video journalism, including many from the 40 videos a week produced by Global Video.

Here are a few examples of trends in online video journalism and innovations using emerging technologies.

Documentary: Just as long-form journalism has a place in the digital sphere, so too do long-form video documentaries using TV and cinema conventions of storytelling.

For example, here is the Guardian’s 32 minute ‘I will never be cut’: Kenyan girls fight back against genital mutilation, which recently won a Webby award.

Web native: As online video has developed, it has found its own style and some filmmakers are telling stories using a new set of rules. Multimedia producer Adam Westbrook has written many articles arguing for online video to encourage subjects to look directly at the camera, abandon the “noddy” (the way video often hides an edit by showing a clip of the interviewer nodding) and instead add a flash to white or black, acknowledging the edit to the viewer.

Storytelling: With the advent of online came new storytelling techniques such as audio slideshows, graphics and ways of visualising data. The BBC Global Video unit has its own fantastic examples, including this video made by Tom Hannen using Adobe After Effects and brilliantly telling the story of blood doping.

The Economist too is experimenting with storytelling in words. Here is an example.

Videos filmed on small, cheap cameras: The Global Video unit itself is equipping its journalists in the field with video news gathering skills. Elise Wicker from the department has written about how she has been training staff overseas to use Kodak cameras to capture footage.

Here is an example of an Al Jazeera documentary filmed entirely on an iPhone. Syria: Songs of defiance is a first-person film made by a journalist who spent many months in Syria but could not risk being seen with a video camera. This film, complete with time lapses shows how a great film can be made in the process of the edit.

Contextual video: Advances in web browsers allow new possibilities. Here are three examples made using Popcorn JS, a JavaScript open-source library from Mozilla allowing video to link to real-time web content such as tweets, Google Maps and Wikipedia entries.

History in the Streets is an audio recording uploaded to SoundCloud with locations linked so that when the audio refers to a place, the viewer is taken to that location on Google Street View and can navigate and explore.

Open Images, Open Data is a Dutch film showing a video surrounded by real-time links to content from several sites, including Wikipedia.

This example of a film about freedom of the press in France links to the source documents, demonstrating how journalists can link to data or research to back up a claim.

Development of Mozilla’s Popcorn Maker tool could allow video journalists without coding skills to produce similar video.

How will audiences be finding and sharing content?

Social sharing is key to the future of video and the format lends itself to a social experience with YouTube demonstrating how videos can go viral.

Social is overtaking search as a way to discover content. Facebook overtook Google in March as a traffic driver to the Guardian, largely down to the news outlet’s “frictionless sharing” Facebook app.

New audiences will be finding and frequently watching video on social networks, whether they be Facebook, Twitter, or Chinese site Renren.

Video is often a component of a wider narrative too. Storify is a free tool allowing anyone to curate a story by dragging in tweets, Flickr photos, SoundCloud audio and video from YouTube and Vimeo.

And platforms such as Storify, YouTube, Vimeo, Bambuser, and many more have their own communities and networks too.

Here is an example of what Mark Boas, one of the Knight-Mozilla Fellows, is doing. He is embedded within the newsroom of Al Jazeera and looking at how you can socially share content without detracting from the experience of viewing a video.

Boas told me that part of what is driving this is social, partly the second screen, partly web-enabled TV, partly browser technologies.

He is experimenting with social sharing text from within The fight for Amazonia. Content is pulled live from a Google Doc, he explained.

Writing on his blog, Boas describes the possibilities of social.

Technology is available now to allow people to chat and comment over the web. Certainly this is an experience we could build in. Imagine if you could see all the people currently watching the same programme as you and interact with them.

Boas believes this social layer is key but that it should not “significantly distract from the main content”.

He thinks the social experience benefits from integrating existing social networks and will “perhaps create new ones surrounding the video medium”.

People like to share their experiences in general and this certainly seems to hold true of video and media in general.

He has ideas for future implementations, including “the use of word accurate hyperlinked transcripts, full support for mobile devices and second-screen synchronisation.”

In an email Boas told me:

I think many like me are experimenting just now. I myself am very interested in making experiences that don’t distract too much from the principle act of watching video but I feel that the challenge here is to allow the viewer to choose the level of interactivity and make that choice as plain as obvious and seamless as possible.

3. What will people be watching video on?

Web-enabled TV: Web technologies and television are converging with the advent of web-enabled TV.

The New York Times earlier this month asked “Why can’t TV navigation be more like a tablet?” That looks likely with the next generation of viewing options, including video on demand available on games consoles and an increasing number of TV apps.

Web-enabled TV is expected to offer users an experience more like navigating using a tablet, with viewers able to control the screen by a series of touch screen gestures and swipes.

If rumours of the new Apple TV are to be believed, this may take the form of a Siri voice-activated TV made by Apple (a later development than Apple TV, a box which is plugged into a regular TV to stream iTunes content).

It is also reported that set-top manufacturer LG will be offering televisions with Google TV later this month, with features including voice activation, the ability for viewers to watch video-on-demand content and web videos and control of content by touch screen and swipes.

Google TV will also allow friends or contacts in different locations to watch video together as it will incorporate Google Hangouts, the Skype-like video option from Google Plus.

Desktops/laptops: BBC Global Video’s audience may access content on different connections than those that spring to mind when you first think of web video.

The number of home broadband connections are low in some of the countries covered by the 27 language services, with large proportions of audiences connecting with dongles and other 3G connections in some countries. Video may be easier to stream on a 3G connection at certain times of the day, and impossible at busier times.

Audiences may also use proxies to circumvent internet restrictions in countries such as China, which can give a slow connection.

Tablets: Tablets are increasingly popular in some of the countries served by BBC Global Video, and take-up is low in other countries.

Whether they become an important platform in poorer countries remains to be seen but there is no doubt that they have already become important for more affluent audiences.

And tablets can provide a beautifully tactile viewing experience, with readers encouraged to use the touch screen to play a video embedded within a news story.

Mobile: The popularity of mobile and likelihood of possibilities for video viewing should not be ignored.

It is worth noting that 87 per cent of the world population has a mobile phone, compared with just 8.5 per cent having fixed broadband. According to stats on Mobithinking, there are 5.9 billion phones compared with half a billion fixed broadband connections.

In Jordan the number of mobiles exceeds the population with 6.2 million phones to 6 million people, according to Ayman Salah, a technology expert based in the Middle East.

In Egypt there are 74 million mobiles for a population of 84 million, Salah said, with mobiles being introduced commercially in 1997. That compares with 11 million landlines, first introduced almost 100 years ago in 1920.

The BBC World Service sites and BBC.com are well served by mobile sites that recognise the phone type and format video accordingly.

But of course mobiles are not all Androids, BlackBerrys and iPhones. Smartphones are less common in poorer countries, and different brands dominate. According to the Economist, Nokia ranks with Coca-Cola as Africa’s most recognised brand.

So what is the future of video in Africa if smartphone penetration is low? I asked mobile expert Peter Paul Koch (also known as PPK online).

“Don’t focus too much on smartphones,” he warned.

Today’s feature phones are getting more and more functionality, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they add video in the near future. The line between smartphones and feature phones is blurring, and pretty soon we’ll see “feature phones” (as in cheap) with “smartphone” functionality.

And video is growing on mobile. Cisco predicts that two-thirds of the world’s mobile data traffic will be video by 2016.

Mobile video will increase 25-fold between 2011 and 2016, accounting for over 70 percent of total mobile data traffic by the end of the forecast period.

Mobile is intimate. It is in your pocket, it is personal and is there when you have a spare five minutes to watch a web video.

What is the future of video? With a growing trend in social sharing, an ever-expanding range of devices and internet connections, including to mobile, the future is bright.