This is the third in a series of six blog posts by Adam Westbrook, each with six tips for the next generation of freelance multimedia journalists, republished here with permission.

Follow the series at this link or visit Adam’s blog.

Storytelling

A lot of the focus for multimedia journalists and digital journalists has been on new technology: using Twitter, learning Flash. But there’s a danger that in the rush to learn new skills, we forgot (or never learn) the oldest ones. And there is no skill older, or more important, than storytelling.

Maybe you think it’s something you can’t learn; it comes naturally. You might think it’s something with no rules: each story is different. True, but there is a science to storytelling as well as an art: here are six secrets.

1) Who’s your character?

Every story needs a character. Lord of the Rings has dozens, but your short doc or audio slideshow might only have one. Either way, they need to be compelling and they need to be embarking on a journey. And we need to like them or be fascinated by them, because we’re going to follow their journey: and we want our audience to follow it too.

No matter what your story, it needs a character. In old-media land this is known crudely as the ‘case study’. (Think how many TV news reports start with a case study!). But they are crucial because they humanise what might actually be a general issue. Making a doc about homelessness? You best make sure it stars a homeless person.

Beware though the difference between ‘character’ and ‘characterization’. Robert McKee in his excellent book Story tells us the latter is the outward description of a person – their personality, age, height, what clothes they wear – but character is the true essence of the person in the story. That true character is only revealed when their journey puts them under increased pressures.

The decisions we all make under pressure are the ones which reveal our true character.

2) The narrative arc

The next thing you want to do is find your story’s narrative arc. Remember I mentioned your character’s journey? Well, that’s your narrative arc.

It starts with what Hollywood screenwriters call ‘The Incident Incident’. It’s the moment which instills in your character a desire to achieve a seemingly insurmountable goal/object of desire. It sets them on a mission – a quest.

This mission must challenge them in increasingly difficult ways (and never decreasingly), rising to a climax to which the audience can imagine no other. Writing in the Digital Journalist, Ken Kobre sums it up:

“Besides a beginning, middle and end, a good story has a memorable protagonist who surmounts obstacles en route to achieving a goal that we care about.”

Stories work better with a real play-off of positive and negative charges. Something good happens, and then something bad. Then something even better than before, and then something even worse than before. Robert McKee describes a second device, called ‘gap of expectation’: that’s where your character’s expectations of an event are blown apart by reality.

3) Oi! Where’s the conflict?

You’re making a film about that homeless person on a mission to get his life back on track. The first thing he wants to do is get some money for a small flat. He asks the council. They give him the money. The end.

Lame story.

Why? Because there is no conflict! I hate conflict in real life, but in storytelling it’s essential. There must be forces opposing your character and their mission. And sparks must fly. McKee lists three types of conflict:

- Inner conflict: your character is in conflict with themselves (Kramer vs Kramer)

- Personal: your character’s in conflict with people around them (Casablanca)

- Extrapersonal: your character’s in conflict with something massive (Independence Day)

4) Climax!

Traditionally stories end in a climax. The ever increasing ups and downs culminate in either an ultimate high (happy ending) or ultimate low (sad ending). Either way, the key word is ‘ultimate’. In Hollywood-land the ending must be so climatic they cannot possibly imagine another way of doing it.

In the real world it is not always the way, but you should have half a mind on how your story is going to end. Crucially if they’ve been set off on a quest, they should finish it for better or worse. The ending should still be ‘absolute and irreversible’.

5) Use tried and tested storytelling techniques

There are lots of little storytelling devices you can use to add some sparkle to your work.

- Book-ending: returning the character/place/event which opened your piece, at the end, is a nice way to sum up what’s changed. It can add a bit of emotional punch too.

- Narrative hook: opening the piece with an enticing, unexplained event/interview/image to suck the viewers right in

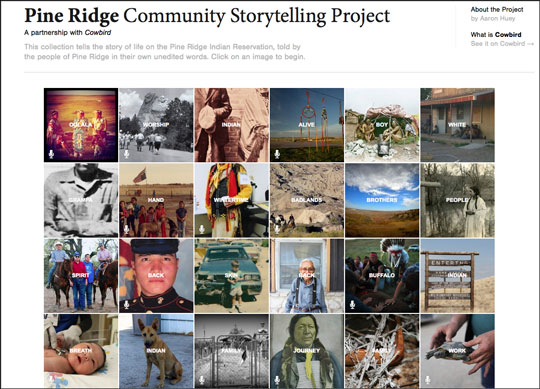

- Get the crayons out: popular in internet memes everywhere, getting people to write something down and hold it up to the camera is very effective (just check out SOTM if you need proof); I know of a very experienced reporter who took crayons and paper to a refugee camp and got children to draw the terrible things they’d seen: another great device.

6) Stories are everywhere!

These guidelines are really used by authors, and screen writers – people who create stories from scratch. As journalists we aren’t making up stories (hopefully not, anyway) – but we should have our eyes and ears open to these elements in the real world to heighten the sense of story for our audience.

And most of all – remember stories are everywhere! I have never been more inspired than by reading Cory Tennis’ advice to one floundering journalism graduate, unable to get work:

“And then, with the irony that cloaks us against utter nihilism, we think, if only we were living in more interesting times! And that is the confounding thing about it, isn’t it? That we stand on the nodal point of a great, creaking, crunching change in historical direction, at the beginning of cataclysmic planetary collapse, at the dying of civilization, at the rising of new empires, at our own meltdown, as a million stories bloom out of the earth like wildflowers in the spring and we think, gee, uh, if only there were some good stories to tell.”

The best way to learn the craft of storytelling, is to get out there and tell some.

The final word:

“A storyteller is a life poet, an artist who transforms day-to-day living, inner life and outer life, dream and actuality into a poem whose rhyme scheme is events rather than words – a two-hour metaphor that says: Life is like this! Therefore a story must be abstract from life to discover its essences, but must not become an abstraction that loses all sense of a life-as-lived. A story must be like life, but not so verbatim that it has no depth or meaning beyond anyone in the street.”

Robert McKee, ‘Story’