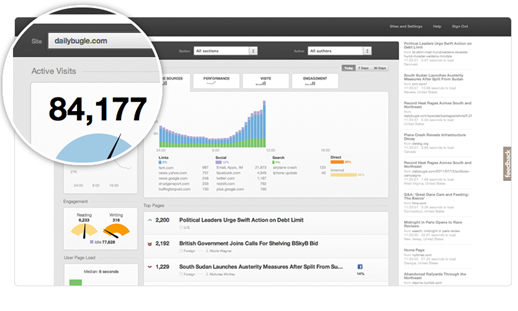

A post on TechCrunch suggests tools such as Google Analytics do not give a true picture of the traffic drivers to your news site.

This post by Jonathan Strauss argues Twitter drives perhaps four times as much traffic to sites than Google Analytics suggests.

It demonstrates how Twitter traffic may be categorised separately by Google, such as when it originates from the tweet button and when it is via Twitter.com.

The article goes further and explains that Twitter may act like a TV ad to provide the drip, drip effect of product (or news story) awareness.

This happens with other marketing campaigns, too. Often you hear a radio ad, see a TV ad or read an article in a magazine and you type the results into Google to find out more details about the product or service. The problem is that marketers assume that Google drove the traffic. They did not. So you ramp down your TV or print campaigns and suddenly your search volume goes down.

The post also questions whether LinkedIn should be seen as such an important traffic driver after this post on TechCrunch reported LinkedIn drives more traffic to its site than Twitter.

Many tweets are now being sent to LinkedIn and then the publisher assumes that the source of the referral is LinkedIn. In some ways it is because that’s where your user engaged the content. But get rid of the tweet and you get rid of the referral traffic in the same way as I described the loss when you cancel your TV commercial.

So when I see MG Siegler announce that LinkedIn is sending more traffic to TechCrunch than Twitter – I’m not so sure. I understand why he would think that – Google Analytics tells him so. But I’ll bet a hefty amount of LinkedIn clicks were originated on Twitter. And I’ll bet a whole lot of TechCrunch “direct” traffic is from Twitter.

LinkedIn may be powered by Twitter and that should be recognised. LinkedIn Today should not be discredited so easily, however. Success for a site with LinkedIn Today depends on it striking a deal with the business development team at LinkedIn and becoming one of its preferred industry sites.

Getting your news on LinkedIn’s aggregated news site which launched in March makes a notable difference. BBC News is one of the sites on LinkedIn Today and has seen a tenfold rise in traffic in the last six months, rising from around 20,000 referrals in January to more than 200,000 referrals from LinkedIn in June.

In order to get a clear picture of your social referrals, the article on TechCrunch states you need a unique URL for each share behaviour.

So if you click on a ‘tweet this’ button on a website to send an article to your friends, that link needs to be individual to you and to that exact share instance. By making the URL link unique to its point of generation you can then track it better as it spreads to other sites.

And importantly when anybody else then shares the link to this site it maps out a “parent/child” link relationship. So if the original tweet was on Twitter and then somebody builds a ‘tweet this’ from a product like LinkedIn, you can still tell that the original source of the the story was Twitter. Call it, “last mile social media attribution” and when you’re a brand spending money on products and marketing you need to know this.

Many sites understand the exact value that reader brings. And if, say, a referral from Facebook or Twitter results in less time on the site and fewer page views than a reader coming via Google, they are less valuable to you if you make your money through advertising.

At a recent conference organised by ABC, Ashley Friedlein, CEO and founder of Econsultancy explained how his firm has given a monetary value to each reader coming via Twitter, Facebook, email referral, direct mail, etc. A referral from Twitter for consultancy is worth 11 pence, a reader coming from an email is worth 58 pence, and direct mail brings a higher value to the company, Friedlein explained.

It is clear that much depends on having very accurate analytics. The TechCrunch article suggests awe.sm, another option is Twenty Feet.

But it’s worth remembering that “the story is never quite as simple as the data might lead you to believe”, as Strauss said in the TechCrunch post.