Yesterday’s Media Standards Trust data and news sourcing event presented a difficult decision early on: Whether to attend “Crowdsourcing and other innovations in news sourcing” or “Open government data, data mining, and the semantic web”. Both sessions looked good.

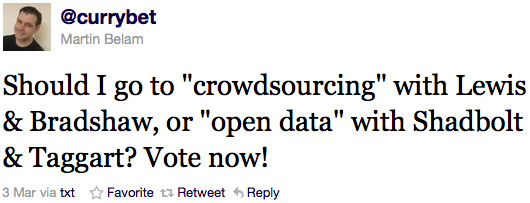

I thought about it for a bit and then plumped for crowdsourcing. The Guardian’s Martin Belam did this:

Belam may have then defied a 4-0 response in favour of the data session, but it does reflect the effect of networks like Twitter in encouraging journalists – and others – to seek out the opinion or knowledge of crowds: crowds of readers, crowds of followers, crowds of eyewitnesses, statisticians, or anti-government protestors.

Crowdsourcing is nothing new, but tools like Twitter and Quora are changing the way journalists work. And with startups based on crowdsourcing and user-generated content becoming more established, it’s interesting to look at the way that they and other news organisations make use of this amplified door-to-door search for information.

The MST assembled a pretty good team to talk about it: Paul Lewis, special projects editor, the Guardian; Paul Bradshaw, professor of journalism, City University and founder of helpmeinvestigate.com; Turi Munthe, founder, Demotix; and Bella Hurrell, editor, BBC online specials team.

From the G20 protests to an oil field in Angola

Lewis is perhaps best known for his investigation into the death of Ian Tomlinson following the G20 protests, during which he put a call out on Twitter for witnesses to a police officer pushing Tomlinson to the ground. Lewis had only started using the network two days before and was, he recalled, “just starting to learn what a hashtag was”.

“It just seemed like the most remarkable tool to share an investigation … a really rich source of information being chewed over by the people.”

He ended up with around 20 witnesses that he could plot on a map. “Only one of which we found by traditional reporting – which was me taking their details in a notepad on the day”.

“I may have benefited from the prestige of breaking that story, but many people broke that story.”

Later, investigating the death of deportee Jimmy Mubenga aboard an airplane, Lewis again put a call out via Twitter and somehow found a man “in an oil field in Angola, who had been three seats away from the incident”. Lewis had the fellow passenger send a copy of his boarding pass and cross-checked details about the flight with him for verification.

But the pressure of the online, rolling, tweeted and liveblogged news environment is leading some to make compromises when it comes to verifying information, he claimed.

“Some of the old rules are being forgotten in the lure of instantaneous information.”

The secret to successful crowdsourcing

From the investigations of a single reporter to the structural application of crowdsourcing: Paul Bradshaw and Turi Munthe talked about the difficulties of basing a group or running a business around the idea.

Among them were keeping up interest in long-term investigations and ensuring a sufficient diversity among your crowd. In what is now commonly associated with the trouble that WikiLeaks had in the early days in getting the general public to crowdsource the verification and analysis of its huge datasets, there is a recognised difficulty in getting people to engage with large, unwieldy dumps or slow, painstaking investigations in which progress can be agonisingly slow.

Bradshaw suggested five qualities for a successful crowdsourced investigation on his helpmeinvestigate.com:

1. Alpha users: One or a small group of active, motivated participants.

2. Momentum: Results along the way that will keep participants from becoming frustrated.

3. Modularisation: That the investigation can be broken down into small parts to help people contribute.

4. Publicness: Publicity vía social networks and blogs.

5. Expertise/diversity: A non-homogenous group who can balance the direction and interests of the investigation.

The wisdom of crowds?

The expression “the wisdom of crowds” has a tendency of making an appearance in crowdsourcing discussions. Ensuring just how wise – and how balanced – those crowds were became an important part of the session. Number 5 on Bradshaw’s list, it seems, can’t be taken for granted.

Bradshaw said that helpmeinvestigate.com had tried to seed expert voices into certain investigations from the beginning, and encouraged people to cross-check and question information, but acknowledged the difficulty of ensuring a balanced crowd.

Munthe reiterated the importance of “alpha-users”, citing a pyramid structure that his citizen photography agency follows, but stressed that crowds would always be partial in some respect.

“For Wikipedia to be better than the Encyclopaedia Britannica, it needs a total demographic. Everybody needs to be involved.”

That won’t happen. But as social networks spring up left, right, and centre and, along with the internet itself, become more and more pervasive, knowing how to seek out and filter information from crowds looks set to become a more and more important part of the journalists tool kit.

I want to finish with a particularly good example of Twitter crowdsourcing from last month, in case you missed it.

Local government press officer Dan Slee (@danslee) was sat with colleagues who said they “didn’t get Twitter”. So instead of explaining, he tweeted the question to his followers. Half an hour later: hey presto, he a whole heap of different reasons why Twitter is useful.