This article was originally published on the European Journalism Centre site. It is reposted here with permission.

This is the first of a two-part report on the Digital Agenda Stakeholders Day, an event held by the European Commission in Brussels on 25 October 2010. Part one of The EU’s digital agenda: What is at stake? looks at some of the overarching issues that most areas of information and communication technology (ICT) have in common. Part two (published Wednesday 27 October, 2010) will put the EU’s Digital Agenda into its political context, and will include a review of the actual Stakeholders Day event.

The first of the common issues is easy and ubiquitous access to secure and dependable communication networks in the first place.

It is not only internet addicts who suffer from being either disconnected or having only unstable or slow connections at their disposal. Already, many amenities of daily life require you to be online; just think of home banking, online shopping, or real-time news.

But the importance of networks for business and society is even greater. While a private person can still manage offline – albeit increasingly worse – industrial production, transport, trade, banking or political decision-making cannot.

In fact, almost every ‘intelligent’ service requires access to either a comprehensive database, sensors, or supercomputing capabilities, or all of the above: traffic management, on-the-fly speech translations, image recognition or health diagnostics, and that’s just for starters.

It is therefore paramount that the best possible network access is provided literally everywhere at an affordable price; that the quality of the infrastructure does not solely depend on whether building and operating it generates a profit for the respective provider, and that it is always up and running.

However, providing a universal service frequently requires public regulation, as high set-up costs favour monopolistic structures meaning less-densely populated areas would otherwise be left behind.

Network neutrality

The second tenet at stake is network neutrality. Basically, this means that the technical infrastructure carries any information irrespective of its content.

In Internet circles, this is known as the end-to-end principle. It is a bit like public roads which you may use with any type of car, bike, lorry, or as a pedestrian. The street does not care what load you are hauling.

Now imagine if one car manufacturer owned the streets and arranged it so only their models have priority clearing traffic jams or passing traffic lights. Or imagine that transporting some products would be banned because shipping others was more profitable to the road owners.

On the other hand, there are motorways to complement surface roads, and restrictions for their use apply. Slow-moving vehicles and pedestrians are banned in order to speed up transport and render it safer for all who are allowed to participate.

Only few people would really want bicycles on highways. Such is the dilemma of net neutrality: You do not want your provider to slow down Google or BitTorrent to prioritise other services, but at the same time you expect your Skype calls or television programmes to be judder-free no matter what.

As a consequence, net neutrality must follow clear rules. For instance, it must be completely transparent. The customer must know what he/she is getting before signing up for a subscription, and if there is no variety of providers available they must have a choice between different, clearly defined plans.

And while the plan that suits the customer best might be a bit more expensive, it must still remain affordable (see ‘universal access’ above).

Also, any kind of network traffic management that amounts to constrictions of pluralism, diversity and equal opportunities in business or social life is unacceptable, too. Net neutrality regulation must safeguard and support competition on both ends, with network providers and third parties.

Net neutrality is, by the way, also a safeguard against censorship and oppression. Just as the post office is not supposed to read your letters, neither is a technical service provider for Internet access or storage.

The fact that it is pretty easy to monitor content and the path of electronic traffic and to retain telecommunications data does not mean it is all right to do so, irrespective of how tempting it may be, as for instance the German Constitutional Court has ruled. Where necessary, criminal offenses must be investigated at the ends of the communication network, not within it.

A contentious issue in this context are the international ACTA treaty negotiations against counterfeiting of physical products and copyright infringements over the Internet, which may entail that Internet service providers become liable for the content moving through their infrastructure.

In that case providers would be required to closely watch content itself, thus effectively snooping on their customers.

Following earlier criticism by the European Parliament, Trade Commissioner Karel de Gucht recently indicated a more guarded stance of the European Commission in the face of the strict ICT-related regulations demanded mainly by the United States.

Standards and interoperability

The third main factor to be taken into account is interoperability. Remember the time when you could not easily open a document that was created with a Mac on your PC, and vice versa?

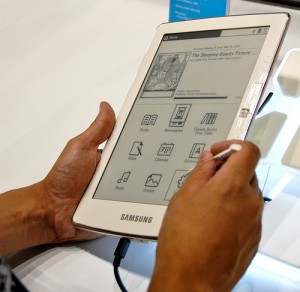

While this specific problem has long disappeared, there are myriad other incompatibilities. The traffic updates you find on a website may not work on your particular navigation system; your health record may not be readable once you are abroad; the e-book you have bought with your old reader refuses to appear on your new one; a database that is important for your business cannot be converted into the format you need; and so on.

There may even substantial new barriers be coming up, for instance if Intel adopts Apple’s App Store model to control what kind of software runs on your run-of-the-mill PC.

The huge success of the Internet so far is not least based on its universal standardisation. The same goes in principle for car fuels, the Euro, credit cards, computer operating systems, mobile phone service, and many more. Standards and so-called ‘open APIs’, or easily accessible, transparent interfaces between software solutions or technical appliances, render a single device, website, or application larger than itself because it can interact with others, exchange data, and inspire entirely new uses through innovative combinations of functionality.

Interoperability also encourages competition, allowing users to combine solutions by different manufacturers, or to freely buy third-party peripheral equipment.

Standards must however be agreed upon very carefully, as they may freeze a given state of the art and discourage further development. Only intelligently defined standards are the essence of innovation, dependability, and pervasiveness.

Content

A related aspect that could be subsumed under interoperability is the current national fragmentation of markets.

While it has become pretty easy to order physical goods or services across European borders, the same does not hold true for intangible, electronic products such as computer software, or content such as e-books, movies, TV programmes, music, etc.

You can buy a DVD or a book anywhere and bring it back home, but you will rarely be able to legally download that same movie from a website in the very same country. This is not so much a technical problem, but rather a legal and social one – content is still licensed on national level rather than European, and it remains difficult to gain access to different language versions of the same content irrespective of the user’s whereabouts.

Similarly, many cultural items such as books, paintings, sheet music, music recordings, motion pictures, etc. cannot even be accessed domestically (not to mention Europe-wide) since the rights are either unresolved or entirely unaccounted for.

The latter are the so-called ‘orphan works’, which are technically copyrighted but where it is impossible to identify any person who actually holds the rights.

The EU-sponsored Europeana project is a large-scale initiative to overcome these issues by collecting legally cleared digitized cultural content from many (mostly public) Member State organisations or cross-border thematic collaborations, and cross-referencing them by context.

At the same time, online content is increasingly threatened by the Fort Knox problem. Data are aggregated under the auspices of an ever smaller number of large-scale organisations such as Google, Apple, or Amazon, to name only a few.

The infamous example of Amazon deleting because of rights issues, of all things, George Orwell’s novel 1984 from Kindle readers who had stored a legally acquired copy, shows quite alarmingly what might happen. Imagine that one entity could delete all copies of a physical book worldwide at will by a mere mouse click!

However well justified and ultimately inconsequential Amazon’s decision about this particular ebook may have been, the incident just goes to show that invaluable data may be lost forever. This may happen just because a single authoritarian government orders its erasure for political reasons, or because the keeper of the file suddenly turns ‘evil’, experiences a trivial thing as a technical breakdown, or goes bankrupt.

Therefore, content storage and control, particularly of any material that is already in the public domain or destined to go there in the future, must be as widely distributed as possible.

While it is highly laudable for example, that Google systematically scans and stores books from university libraries, none of the participating libraries should let Google hold the only electronic copy of their books.

Security and privacy

In addition to all the above, there are overarching concerns related to security and privacy in the ICT area, and they overlap with the other main tenets – or sometimes even run contrary to them.

Cyber crime and hacker attacks on the infrastructure or individual devices must be combated without compromising the principles of a free network, standards, and interoperability.

Freedom of information must be balanced against the right to privacy, and while the former requires safeguarding that stored data remain accessible, the latter may even entail that information gets intentionally deleted for good.

Security of supply and integrity of the infrastructure need technical provisions which may be at odds with commercial or law enforcement interests. Online communications of importance and sensitive data transfers must be trustworthy and authentic.

Spam, viruses and other nuisances must be neutralised – all without rendering ICT networks and components too inconvenient and cumbersome to use. The list goes on.

Please return for the second installment of this report (published Wednesday 27 October, 2010), where I discuss the Digital Agenda’s background in the European Union’s policy. Part two will be accompanied by a downloadable summary of the actual Digital Agenda Stakeholders Day.

Related articles on Journalism.co.uk:

The campaign to repeal the Digital Economy Act and why journalists should pay attention

Campaigners call for ongoing protest against Digital Economy Act

Pingback: Eric Karstens – The EU’s Digital Agenda (part I): What is at stake?